May 30, 1922: The Words Not Spoken

- abesgirl

- May 13, 2022

- 4 min read

Updated: May 14, 2022

By Wendy Swanson

Washington, D.C.

Friday, May 13, 2022

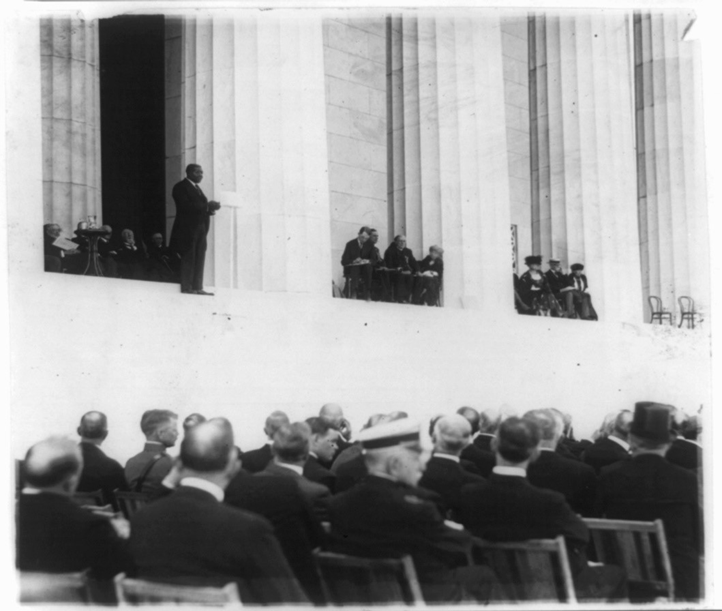

Robert Moton gives his keynote address at the Lincoln Memorial Dedication.

(Editor's note: This is the second in a series of three blogs that tell the story of the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial in 1922. The three blogs originally appeared as a single article in the Winter 2022 edition of the Lincoln Group's Lincolnian newsletter.)

The Speeches: Although the keynote speaker at the 1922 Lincoln Memorial dedication, Robert Moton was not given free rein to speak as he chose on all the issues he considered pertinent. Prior to the dedication, he was asked to submit his speech for review. After doing so, he received the following correspondence from Chief Justice Taft, acting in his capacity as chairman of the Lincoln Memorial Commission. That telegram, dated May 23, 1922, insisted on revisions to the proposed draft:

Will have to ask you to cut five hundred words, and suggest that in making the cut you give more unity and symmetry by emphasizing tribute and lessening appeal. I am sure you wish to avoid any insinuation of attempt to make the occasion one for propaganda. Our personal relations make me feel that you will understand the motive in the suggestion. Wm. H. Taft

Organizers of the event censored significant content of the proposed speech as too radical; a milder version was demanded. Sections of the address considered to be “problematic” - and subsequently deleted - referenced failure of the federal government to protect the rights of African Americans. For example, in one deleted section, Moton had referred to Lincoln’s mention in the Gettysburg Address of “great unfinished work” and the need to ensure that “government of the people, for the people and by the people should not perish from the earth.” After quoting Lincoln, Moton had added:

and this means all the people. So long as any one group within our nation is denied the full protection of the law, that task is still unfinished….But unless here at home we are willing to grant to the least and humblest citizen the full enjoyment of every constitutional privilege, our boast is but a mockery…before the nations of the earth…A government which can venture abroad to put an end to injustice and mob-violence in another country can surely find a way to put an end to these same evils within our own borders.

This language on race relations and social justice did not appear in the keynote address given on May 30, 1922. In fact, a significant portion of the final section of Moton’s original speech was revised.

Some may wonder why Moton, working under such restrictions, proceeded with presenting his keynote address. He undoubtedly considered when and if he would have ever again the opportunity to address such a large assemblage (crowd estimates were at 50,000 or more; additional individuals were listening via that new technology, radio broadcasts). Although he made cuts, as required, Moton made certain points clear. He did talk of reconciliation but he also called on the nation to complete the “unfinished work.” He observed that from the day of Lincoln’s tragic death “the noblest minds and hearts, both North and South, were bent to the healing of the breach and the spiritual restoration of the Union.” He also expressed the desire that the memorial’s dedication marked the nation’s renewed commitment “to fulfill to the last letter the task imposed on it by the martyred dead – that it highly resolve that the humblest of citizen of whatever color or creed, shall enjoy that equal opportunity and unhampered freedom for which the immortal Lincoln gave ‘the last full measure of devotion.’” Moton closed by quoting Lincoln’s second inaugural address, adding his own belief:

that all of us, black and while, both North and South, are going to strive on to finish the work which he so nobly began to make America an example for the world of equal justice and equal opportunity for all who strive and are willing to serve under the flag that makes men free.

The audience stood in applause as the band played “America.”

Much has been written about Moton’s censored speech. For those who wish to explore further the revisions made to his original speech, the Library of Congress provides a side-by-side comparison of the two versions of the address. The speech not delivered is also contained in The Lincoln Anthology, edited by Harold Holzer, published by Library Classics of the United States, New York, 2009.

The speeches of Taft and Harding repeated the original focus of the memorial as a symbol of the unification of the previously divided nation. To Taft, the monument signified “the restoration of brotherly love of the two sections” previously divided, e.g., North and South. Thus, he found the site selected for the memorial, on the Potomac, “the boundary between those two sections, peculiarly appropriate.” In fact, according to the Chief Justice, Lincoln was “as dear to the hearts of the South as to those of the North.” Harding offered remarks that dovetailed those of his predecessor – “how it would soften his (Lincoln’s) anguish to know the South long since came to realize that vain assassin robbed it of its most since and potent friend.”

Harding started his remarks by accepting on behalf of the government the monument to the savior of the republic. Again the focus was unification with no reference to what we today consider a major part of the Lincoln legacy, that is, as the Great Emancipator. In fact, Harding essentially considered emancipation as a “means to the end:”

The supreme chapter in history is not emancipation, though that achievement would have exalted Lincoln throughout all the ages. The simple truth is that. Lincoln, recognizing an established order, would have compromised with the slavery that existed, if he could have halted its extension. Hating human slavery as he did, he doubtless believed in its ultimate abolition through the developing conscience of the American people, but he would have been the last man in the republic to resort to arms to effect its abolition. Emancipation was a means to the great end—maintained union and nationality.

To be concluded. Coming up next: The Reaction

Don't forget to join us on May 22nd on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial for our centennial celebration organized by the Lincoln Group of DC and National Park Service and co-sponsored by the Lincoln Forum. And check out all the other events we have going on this month to commemorate the Memorial's 100th anniversary. [Click on the "Events" tab to see it all]

(Photo credit: Library of Congress)

Comments